Established by group vote on June 26, 2010, the Society's Short Mystery Fiction Hall of Fame honors deceased writers' impact on the mystery and crime short story.

New candidates are considered annually from February 1 to March 30. Inductees, if any, are announced May 1.

Charter Inductees (2010)

Subsequent Inductees

| Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) |

|---|

One of the most important of all American literary figures, Poe wrote poetry and book reviews, and edited magazines, in addition to writing short fiction. His stories covered a variety of genres, but he is best-remembered as nothing less than the inventor of the crime fiction genre.

More than that, in just a few short stories, he laid the foundation for most of the conventions now associated with that genre. In "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841), "The Mystery of Marie Roget" (1842), and the "The Purloined Letter" (1844), the three stories comprising the trilogy featuring brilliant amateur sleuth C. August Dupin, Poe established the series character as the bulwark of the genre; introduced the device of having the stories narrated by an admiring friend of the hero, thus anticipating characters like Dr. Watson, Captain Hastings, and Archie Goodwin; depicted his hero as an "armchair detective" who was able to solve difficult cases without leaving his room just by the information he was given, a device that would later be used by Baroness Orczy and Rex Stout; wrote the first locked-room mystery, setting the stage for writers like John Dickson Carr, Joseph Cummings, Joel Townley Rogers, and Edward D. Hoch; introduced espionage as a sub-genre of crime fiction, providing a model for writers as diverse as Ian Fleming, Dorothy Gilman, and John le Carré; fictionalized a real-life crime, thus anticipating stories ranging from Marie Belloc Lowndes's novel The Lodger, inspired by the Jack the Ripper murders, to James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, both loosely based on the murder of Albert Snyder by his wife and her lover, to the radio-TV series Dragnet, every episode of which was based on an actual police case with "the names changed to protect the innocent"; had, as a recurring character, a well-meaning but plodding official policeman whose lack of imagination contrasted with the intellectual agility of the gifted amateur, anticipating characters like Inspector Lestrade, Inspector Japp, and Sergeant Holcomb; and created a brilliant master criminal to pit against his brilliant master detective, prefiguring characters like Professor Moriarty, Dr. Fu Manchu, Arnold Zeck, and Ernst Stavro Blofeld.

In stand-alones like "The Gold Bug" (1843), "The Tell-Tale Heart" (1843), "The Black Cat" (1843), and "'Thou Art the Man!'" (1844), he introduced the device of a code or cipher as a clue to the solution of the case, anticipating stories like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's "The Adventure of the Dancing Men" and Dorothy L. Sayers's Have His Carcase; took us inside the minds of murderers, anticipating works like Francis Iles's Before the Fact and Jim Thompson's The Killer Inside Me; used a courtroom scene to heighten suspense, anticipating dozens of legal thriller specialists like Erle Stanley Gardner, Scott Turow, and John Grisham; used the device of a wrongfully accused suspect whom the detective must work to clear, the central theme of novels like William Irish's Phantom Lady and Agatha Christie's Mrs. McGinty's Dead; revealed the hitherto unknown villain to be the least suspected person, a surprise twist that virtually every whodunit writer since Poe has tried to replicate; and used methods of psychological pressure to trick a confession out of that least suspected person, anticipating scores of interrogation scenes and cross-examinations in modern police procedurals and courtroom thrillers.

In short, Poe laid the groundwork for so many of the tropes and traditions now commonly associated with our genre, that he left successors with, to quote Conan Doyle, "no new ground they could confidently call their own."

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

| Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) |

|---|

Scottish physician who turned to writing crime fiction to supplement the meager income generated by his London medical practice, he would, in 1884, conceive the notion of a brilliant private consulting detective, patterned to a degree on Poe's Dupin, but closely based on one of his medical school professors, Dr. Joseph Bell, who, by observing minute details, was able to make the same kind of deductions in real life that Dupin made in fiction.

The character Conan Doyle conceived, eventually dubbed Sherlock Holmes, made his debut in the 1887 novel, A Study in Scarlet. A second novel, The Sign of Four, followed in 1890. But it was the series of short stories featuring Holmes which appeared regularly in The Strand that turned the Baker Street sleuth into the most recognized character in fiction. Beginning with the 1891 entry "A Scandal in Bohemia," the soaring popularity of these stories would ultimately turn Holmes into fiction's first multi-media sensation, featured in stage plays, radio dramas, television series, comic strips and books, and, according to The Guinness Books of World Records, becoming the most frequently depicted character in movies, portrayed by more than 70 different actors in more than 200 films.

Conan Doyle would ultimately write 56 short stories featuring Holmes, along with two more novels, two stage plays of his own, and a third play on which he collaborated with famed American actor William Gillette. Those short stories, collected in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892), The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1894), The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1905), His Last Bow (1917), and The Case Book of Sherlock Holmes (1927), are arguably the most popular pieces of short crime fiction ever written. And many, such as "The Red-Headed League" (1891), "The Adventure of the Speckled Band" (1892), "Silver Blaze" (1892), and "The Final Problem" (1893, which introduced arch-fiend Professor Moriarty), are routinely listed as among the finest examples of short mystery fiction ever produced. Holmes's enduring popularity is indicated by the fact that so many writers, including John Dickson Carr, Nicholas Meyer, Edward D. Hoch, Loren D. Estleman, and Stephen King, have all written Holmesian pastiches. Indeed, there are now far more Holmes stories written by other writers than were originally written by Conan Doyle. That fact alone is positive proof of his creation's immortality.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

R. Austin Freeman (1862-1943) |

|---|

Freeman was an English physician whose deteriorating health after colonial postings in Africa forced him to largely give up the practice of medicine, he turned to writing fiction to produce income. His earliest mysteries were a series of short stories featuring Romney Pringle, a charming professional thief in the mode of E.W. Hornung's Raffles or Maurice Leblanc's Arsene Lupin, written in collaboration with another physician, J.J. Pitcairn, under the joint pseudonym of "Clifford Ashdown." The stories were collected in The Adventures of Romney Pringle (1902) and The Further Adventures of Romney Pringle (1905).

On his own, and under his own name, Freeman created his most famous character, Dr. John Thorndyke, physician, barrister, and perhaps fiction's first forensics investigator. Using carefully researched, and wholly accurate (for the time) scientific methods, Thorndyke was able to solve cases that baffled the police. He first appeared in the 1907 novel The Red Thumb Mark. A collection of short stories, John Thorndyke's Cases, appeared the following year. Ultimately, in addition to 20 more Thorndyke novels, Freeman would write five more Thorndyke short story collections, The Singing Bone (1912), The Great Portrait Mystery (1918), The Blue Scarab (1923), The Puzzle Lock (1925), and The Magic Casket (1927). A posthumous collection, The Best Dr. Thorndyke Detective Stories (1973), cherry-picked some of the best stories from the previous volumes and included the first book publication of the 1911 novelette "The Mystery of 31 New Inn."

Of these, the most important collection in the series, arguably one of the most important short story collections in the history of the genre, was The Singing Bone. Each of the stories in that volume is divided into two parts. In the first, told from the point of view of the criminal, the reader sees the murder committed and knows who the killer is. In the second, we see Dr. Thorndyke undertake an investigation in which he tries to figure out what the reader already knows. This grew out of a notion Freeman had of a mystery in which, as he put it, "The reader had seen the crime committed, knew all about the criminal, and was in possession of all the facts. It would have seemed that there was nothing left to tell, but I calculated that the reader would be so occupied with the crime that he would overlook the evidence. And so it turned out. The second part, which described the investigation of the crime, had to most readers the effect of new matter."

This made Freeman, not only the first writer to depict authentic methods of forensic investigations in his crime fiction, but also arguably the inventor of what has come to be called the "inverted detective story,” anticipating writers like Roy Vickers with his Department of Dead Ends series, Cornell Woolrich with novels like Rendezvous in Black (1948) and short stories like "One Drop of Blood” (1962), L.R. Wright's Edgar-winning The Suspect (1985), and, most famously, the long-running TV series Columbo.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

|

| Baroness Orczy (1865-1947) |

|---|

Hungarian-born aristocrat who emigrated to England with her family at the age of 15, the Baroness Emma "Emmuska" Orczy is today best-remembered for her romantic historical adventure stories, particularly those featuring Sir Percy Blakeney, the foppish baronet who fought injustice in the guise of the mysterious swashbuckling hero, "The Scarlet Pimpernel."

But she was also, in the early days of our genre, one of its most important innovators. Her best-remembered detective character was the elderly sleuth known as "The Old Man in the Corner." Introduced in the short story "The Fenchurch Street Mystery" (1901), the Old Man is perhaps the best-realized example of an armchair detective, solving mysterious crimes without ever leaving his seat in a small London teashop. His stories would be collected in The Case of Miss Elliott (1905), The Old Man in the Corner (1909), and Unravelled Knots (1925).

Ranking a close second behind the Old Man is Lady Molly Robertson-Kirk, one of the top detectives in the London Metropolitan Police, and perhaps the first professional policewoman in fiction, whose published adventures actually predated the appointment of London's first women police officers by more than five years. Her twelve cases are collected in Lady Molly of Scotland Yard (1910). Cunning defense lawyer Patrick Mulligan, whose five stories are collected in Skin o' My Tooth (1928), proves his wrongfully accused clients innocent by solving the crimes himself and identifying the actual culprits, precisely the modus operandi adopted by Erle Stanley Gardner's Perry Mason a few years later.

The Baroness combined detective fiction with the swashbuckling historical adventure she is better remembered for in ten stories featuring Monsieur Fernand, an agent of the Imperial Police in Napoleonic France, who was featured in ten stories collected in The Man in Grey (1918). Baroness Orczy's admirable facility at plot, characterization, and sheer style is amazing when one considers that English was a second language that she didn't learn to speak until her family moved to Britain from her native Hungary.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

|

| Raymond Chandler (1888-1959) |

|---|

If Hammett's "The Gutting of Couffignal" is arguably the finest private eye short story ever written and The Maltese Falcon arguably the finest private eye novel, then Raymond Chandler's "Red Wind" (1938) and The Long Goodbye (1954) are the reasons that there's an argument.

American-born and British-raised and educated, Chandler had worked as a journalist in his young adulthood, and had once had ambitions of being a poet. After a stint of WW1 combat duty in a Canadian infantry regiment, he found employment, and affluence, as an oil executive in Southern California. Then, in 1932, the Depression (and, frankly, his own drinking habits) put him out of work.

A fan of crime fiction in the pulps, and particularly of Hammett's work, he became captivated by the creative possibilities of American colloquial speech and by the portrayal of the gritty urban backgrounds in the stories he read, and resolved to try to write the same kind of fiction himself. His first two stories, "Blackmailers Don't Shoot" and "Smart-Aleck Kill," published in Black Mask in 1933 and 1934 respectively, were imitations of the spare third person style Hammett had used in The Maltese Falcon and The Glass Key. They featured a Chicago private eye named Mallory, who relocates two Los Angeles for his two recorded cases. Chandler was not particularly happy with either of these stories, feeling they were too derivative.

He found his own voice in his third Black Mask story, "Finger Man" (1934), which, for practical purposes, introduced his most famous character, Philip Marlowe, the archetype for virtually every hard-boiled private eye character to appear since. At this point, however, the character was, like the Continental Op, nameless. By his third appearance, "The Man Who Liked Dogs" (1936), the character had acquired a last name, Carmady, but was still operating sans a first name. When, in late 1937, Chandler was wooed away from Black Mask by the editors of rival Dime Detective, he brought his character with him, changing his name to John Dalmas. In 1939, Chandler's first novel, The Big Sleep, was published, and the character finally appeared under the name by which he is best-remembered, Philip Marlowe. Altogether Chandler wrote eleven short stories about his private eye character for the pulps. Four of these, the aforementioned "Finger Man" and "Red Wind," as well as "Goldfish" (1936) and "Trouble Is My Business" (1939), were collected in Chandler's short story collection The Simple Art of Murder (1950), with the original names of "Carmady" and "John Dalmas" replaced by "Philip Marlowe." The remaining "Carmady" and "Dalmas" stories were combined and expanded ("cannibalized" to use Chandler's term) into the novels The Big Sleep, Farewell, My Lovely (1940), and The Lady in the Lake (1943).

Chandler once said that he thought book-length fiction suited him better, but his short stories contain some of his best writing, and the opening of "Red Wind," with its haunting description of the hot, dry desert air blowing through the city, is probably the most quoted passage in Chandler's entire corpus. Despite his obvious talent for short fiction, Chandler, motivated by the need to generate an income, largely abandoned stories for novels after The Big Sleep was published.

For a time, he even abandoned novels for movie scripts when he found he could make more money as a screenwriter. But he never lost his love for prose fiction, nor, despite his misgivings about his own ability in the medium, for the short form. He would eventually return to both. His last piece of fiction, taken up after he had abandoned the barely-begun novel Poodle Springs as not worth continuing with, was a short story, the last Marlowe story of any length, and the first Marlowe short story to originally feature Marlowe by name. Most often appearing under the title "The Pencil" (1959, though it has also been printed as "Marlowe Takes on the Syndicate," "Wrong Pigeon," and "Philip Marlowe's Last Case"), it pitted the detective against Mob hit men.

Chandler's stand-alone stories also deserve mention. In addition to his prototypical PI, Chandler wrote about tough cops in stories like "Spanish Blood" (1935) and "Pick-Up on Noon Street" (1936), hotel security officers in "The King in Yellow" (1938) and "I'll Be Waiting" (1939), and ordinary guys dragged into criminal proceedings against their will in "Nevada Gas" (1935). In "Pearls Are a Nuisance" (1939), he satirizes the "gentleman amateur" school of detection as exemplified, in the U.S., by writers like S.S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen. In "No Crime in the Mountains" (1941), published a few months before Pearl Harbor, he combines the private eye story with WW2 espionage.

But the character of Marlowe towers over all of Chandler's other heroes. In addition to the stories Chandler himself selected for The Simple Art of Murder, several posthumous short story collections have been published, among them Killer in the Rain and Other Stories (1964), consisting mainly of stories Chandler "cannibalized" for his novels, which he did not allow to be reprinted during his lifetime, and Collected Stories (2002), which reprints all of Chandler's short fiction, including his stories outside of the crime genre. The dispute over who is the greater writer of hard-boiled private eye fiction, Hammett or Chandler, will probably never be settled. But there can be no denying that, whether or not Hammett was superior, Chandler was, through his creation of a character who would ultimately solidify into the paradigm followed by virtually every PI writer who followed, the more influential.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

| Agatha Christie (1890-1976) |

|---|

Though half-American on her father's side, the woman who is, to this day, more than three decades after her death, one of the best-selling writers in the world, came to epitomize the traditional British "Golden Age" mystery.

In addition to novels and short stories featuring such characters as Belgian-born private detective Hercule Poirot, prototypical "little old lady" amateur sleuth Jane Marple, British Intelligence Agent Johnny Race, "Happiness Consultant" Parker Pyne, crime-solving married couple Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, and others, she wrote more than a dozen stand-alone mysteries; straight fiction as "Mary Westmacott"; the script for one of the very first television plays ever broadcast; radio dramas; and numerous stage plays, some original and some adapted from her prose fiction.

She also wrote more than 150 short mysteries that would ultimately be preserved between hard covers in 20-odd collections, some like Poirot Investigates (1924), Partners in Crime (1929), and Miss Marple's Final Cases (1979), featuring series characters she had developed in novels; others like The Mysterious Mr. Quinn (1930) and Mr. Parker Pyne – Detective (1934), featuring series characters developed especially for short fiction; still others, such as The Hound of Death (1933), The Listerdale Mystery (1934), and When the Light Lasts (1997) consisting of stand-alone stories. Her short fiction has been adapted for stage, screen, radio, and television. "Wasp's Nest," a half-hour TV play adapted by Miss Christie from her identically titled 1928 short story and broadcast on the BBC on 18 June 1937, starred Francis Sullivan as Poirot (a part he had been associated with on the British stage since 1931), and may possibly have been the first dramatic script ever written especially for television.

The Mousetrap (1952), based by Miss Christie on her 1948 short story "Three Blind Mice," has been running continuously in London for nearly 60 years. Witness for the Prosecution (1953), was adapted from her 1925 short story of the same name into one of the most famous courtroom dramas ever staged, earning Miss Christie both a New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Foreign Play and an Edgar for Best Mystery Stage Play, and was, in turn, adapted by Billy Wilder into an award-winning film.

Miss Christie's captivating characters, incredibly ingenious plots, and smooth, even writing continue, years after her death, to make her a favorite with mystery readers all over the world. In 1954, the Mystery Writers of America awarded her a Special Edgar for Lifetime Achievement. In retrospect, the MWA has designated this award as its first ever "Grand Master" presentation, though that title had not yet been coined at the time she received the award, making her the very first recipient of any award, given by any organization, for Lifetime Achievement in crime fiction. In 1956, in recognition of her literary accomplishments, she was made a Commander of the British Empire. The following year, she was elected president of the Detection Club, the first-ever organization of mystery writers, of which she had been a charter member when it was founded in 1930. In 1971, she was promoted to Dame Commander of the British Empire. She is now, and always will be, a legend in our genre.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

|

| Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957) |

|---|

A clergyman's daughter, Dorothy L. Sayers grew up to be one of the first women to earn a baccalaureate from Oxford, which she received, with honors, in 1915. She went on to earn a master's degree from the same institution five years later.

While eking out a meager living at a London advertising agency, she created the character who would make her famous, a wealthy British aristocrat whose surface "Bertie Wooster" persona concealed a broken heart, a combat-hardened resilience, and a brilliant deductive mind. Lord Peter Wimsey, the second son of the fifteenth Duke of Denver, was introduced in her first novel, Whose Body? (1923), and is today chiefly remembered for his 11 book-length cases (12 if one counts the unfinished Thrones, Dominations, 1998, which was posthumously completed by a collaborator), but he also was the star of 20 short stories.

During Miss Sayers's lifetime 17 of the Wimsey shorts were collected in Lord Peter Views the Body (1929), Hangman's Holiday (1933), and In the Teeth of the Evidence (1939). All of these stories, plus three that were never collected during Miss Sayers's lifetime, were gathered together in the massive Lord Peter (1972).

While many series writers use short stories only for comparatively minor, plot-driven episodes in their characters' sagas, Miss Sayers often reserved major events in Lord Peter's life for his shorter appearances. "The Learned Adventure of the Dragon's Head" (1928), told from the point of view of Lord Peter's nephew, St. George Wimsey, gives us some insight into his extended family. "The Adventurous Exploit of the Cave of Ali Baba" (1928), spans two full years, during which Lord Peter is presumed to be dead, but is, in fact, deep undercover infiltrating a powerful organized crime cartel. "The Haunted Policeman" (1938) takes place during the birth of Lord Peter's first son. And in "Talboys" (1972), the final piece of fiction, short or long, that Miss Sayers ever wrote about Wimsey, we see how His Lordship has adapted after several years of life as a settled family man.

Aside from the Wimsey series, Miss Sayers wrote 11 short stories about crime-solving wine salesman Montague Egg, which appear in Hangman's Holiday and In the Teeth of the Evidence, and 12 stand-alone short mysteries. She was also one of the first anthologists of short mystery fiction, editing the classic Omnibus of Crime (1929), as well as three separate editions of Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery, and Horror in 1928, 1931, and 1934, thus insuring that some of the earliest examples of our genre would be preserved between hard covers.

Miss Sayers stands second only to Agatha Christie in the regard she is held by lovers of traditional "Golden Age" mysteries, a level of respect she accomplished this while completing far fewer novels and stories during a far shorter span of time. In fact, many admirers, including P.D. James and Ruth Rendell, noting the depth she gave her characters, her literate style, and her success, at least to a degree, in elevating detective fiction to a level of literary excellence, regard her as superior to Miss Christie as a writer. Though she gave up mystery writing in the early 1940's, devoting the rest of her life to writing religious pieces, her status in the mystery community is, like her character, without peer.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

|

| Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961) |

|---|

While Carroll John Daly's first story featuring a tough, colloquial private eye preceded Dashiell Hammett's by a few months, Hammett is nevertheless recognized and revered, and quite properly, as the founding father of what came to be called "The Hard-Boiled School" of mystery fiction.

That first PI story of Hammett's, "Arson Plus" (1922), featured an anonymous operative of a national investigative and security firm called the Continental Detective Agency (a fictionalized version of the Pinkerton Agency, where Hammett had himself been employed as a detective for many years).

The Continental Op, who told his stories a laconic, spare, sardonic first-person style, was, in some ways, like all of Hammett's heroes, a self-portrait, but, to provide Hammett with some distance, many of the traits of he gave his character were deliberately different. The Op admits to being short (Hammett was over six feet tall), heavy-set (Hammett was cadaverously thin), and 35 to 40 years old (Hammett was still in his 20's when he began the series), a description that more closely matched Hammett's first supervisor at the Pinkerton Agency, James Wright, than it did Hammett himself.

All of the Op stories are excellent, and one, "The Gutting of Couffignal" (1925), is often pointed to as perhaps the finest private eye short story ever written. Most of the Op stories were first published in the legendary pulp magazine Black Mask, and the three novels Hammett wrote about the Op, Red Harvest (1929), The Dain Curse (1929), and Blood Money (1943), were all serialized in Black Mask prior to book publication.

In addition to the Op, Hammett was also the creator of another tough, crafty San Francisco PI named Sam Spade, who debuted in The Maltese Falcon (1930), arguably the finest private eye novel ever written. He followed this with a gritty examination of big-city gangsterism and corrupt politics, The Glass Key (1931), which was his personal favorite of all his books. Like the Op novels, both of these were serialized in Black Mask.

Hammett's final novel, The Thin Man (1934), which introduced the crime-solving husband-and-wife team of Nick and Nora Charles, was the only one of his full-length works which was not serialized in Mask. All of Hammett's novels had short story roots. The Thin Man was expanded from a short story that originally appeared in an issue of Redbook. The Op trilogy and The Glass Key were each deliberately constructed so that each magazine serial installment could stand on its own as a short story. The Maltese Falcon, though written as a single piece rather than a series of loosely connected short pieces, nevertheless recycled plot elements and characters that Hammett had developed in previously written Op stories, including "The Gutting of Couffignal."

In addition to the 26 (not counting the serial installments) Op stories, Hammett wrote three stories featuring Spade, two featuring a decidedly non-hard-boiled private investigator named Robin Thin, and some 30-odd more featuring stand-alone characters, cops, criminals, private eyes, and ordinary people caught up in extraordinary circumstances.

He also reviewed mysteries for such publications as Saturday Review and the New York Evening Post, edited an anthology of short horror stories titled Creeps by Night (1931), doctored dozens of movie scripts (though his name appeared on very few movie credits other than as the writer of the source material), and created Secret Agent X-9, a comic strip about a tough, mysterious FBI agent designed to compete with Dick Tracy.

Some of the collections of his short fiction include The Adventures of Sam Spade (1944), Hammett Homicides (1946), The Big Knockover and Other Stories (1966), The Continental Op (1974), Nightmare Town (1999), Crime Stories (2001), and Lost Stories (2005). For practical purposes, Hammett's entire literary output was produced during a 12-year period between 1922 and 1934. Yet that comparatively small body of work during a comparatively brief span of time is one of the most influential in our genre.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

|

| Cornell Woolrich (1903-1968) |

|---|

Unlike contemporaries Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, who started out in pulps and, by dint of hard work, broke into hard cover books put out by major publishers, the sad, tragic figure whose crime stories and novels would come to be regarded as prototypical exemplars of the noir style began his literary career by writing critically regarded straight novels in the manner of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

The break-up of an ill-advised, short-lived (and apparently unconsummated) marriage and the subsequent publication of his sixth novel, Manhattan Love Song (1932), was followed by a two-year drought during which the young writer sold nothing. Giving up his hopes of a prestigious career as a serious novelist, he turned to the pulps, and to crime fiction, selling his first mystery, "Death Sits in the Dentist's Chair," to Detective Fiction Weekly in 1934. This tale, the first of some 200 short mysteries, and 17 mystery novels, had many of the hallmarks that would come to be associated with Woolrich. Bizarre coincidences, a trenchant depiction of Depression-era New York, a race against time to save a doomed protagonist, and a dark, sinister atmosphere, what Chandler once called "the smell of fear," all elements that would become Woolrich's stock in trade, were all present in that first story.

In Woolrich, there was none of the carefully worked out feats of logic that marked writers like Ellery Queen, none of the matter-of fact, laconic pragmatism of Hammett, none of the breezy, wise-cracking toughness of Chandler. In an amazingly productive decade and a half Woolrich wrote everything from fast-action thrillers like "Hot Water" (1935), to early police procedurals like "Detective William Brown" (1938), from criminal protagonist studies like "Three O'Clock" (1938) to stories with a touch of occult or supernatural elements like "Dark Melody of Madness" (!935), but what set all his fiction apart was unbearable, nail-biting suspense, an impending sense of claustrophobic doom, and uncontrollable randomness.

Coincidence ruled the day in Woolrich's universe. Doom fell on the just and the unjust alike. Some of his stories had happy endings. Some didn't. And if the technical details of his plots often couldn't stand up to even a cursory examination, what did it matter? You read Woolrich for the full-throttle ride, a that ride ended in a fatal crash as often as in a safe stop.

In 1940, Woolrich's first crime novel, The Bride Wore Black, was published, the first of six suspense novels, unrelated save for all sharing the word "black" in the title, culminating in Rendezvous in Black (1948). By 1942, he was producing enough book-length work that it seemed advisable to adopt pseudonyms to accommodate his prodigious output.

"William Irish," a name possibly derived from a screenwriter Woolrich may have met or known of during his own short stint in Hollywood, was the name under which one of Woolrich's most famous novels, Phantom Lady (1942), was published. "George Hopley," derived from his middle names, was used as the byline for Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1945). As his novels became more and more popular, Woolrich was able to develop a market for collections of his pulp stories, such as I Wouldn't Be in Your Shoes (1943), After-Dinner Story (1944), If I Should Die Before I Wake (1945), and Dead Man Blues (1947). Though virtually all of the stories in these collections made their initial magazine appearances under Woolrich's own name, the collections were bylined "William Irish."

In 1949, Woolrich was awarded the second Edgar award ever given in the short story category, apparently for continued general excellence as a writer of short crime fiction. Oddly, perhaps because all of his short story collections to that point had been published under the Irish pseudonym, the prize was awarded to him as "William Irish."

Even more oddly, it was at about the same time he received the Edgar, an event that roughly coincided with the death of his estranged father, that his frenzied productivity came to a sudden end. For the next 20 years, he was able to produce only a tiny fraction of the protean output he'd so easily managed during the previous 15. His income (and it actually wasn't a bad one), mostly derived from adaptations of his work for radio, television, and film, and from collections of previously published short material, like Nightmare (1956) and Violence (1958), now finally appearing under the Woolrich byline.

Two of the most successful dramatic adaptations of his work, the 1949 noir classic, The Window, based on his story "The Boy Cried Murder" (1947), and the Hitchcock-directed Rear Window (1954), based on "It Had To Be Murder" (1942), both came out during this dry period (and, coincidentally, both won Edgars in the screenplay category). What little original short fiction he was able to produce during this period was due largely to the efforts of Frederic Dannay at EQMM and Hans Stefan Santesson at The Saint Magazine, who both made a point of encouraging him to keep writing, but most of it fell below the standards he'd reached during his peak years. Occasionally, though, he was still able to give readers a glimpse of the talent that had made him a legend in the mystery community between 1934 and 1948.

"One Drop of Blood" (1962) is a masterful inverted tale about the battle of wits between a tough cop and a clever killer. "For the Rest of Her Life" (1968), the last story to be published in Woolrich's lifetime, is a harrowing story of the doomed efforts of a brutalized wife to escape her abusive husband. And the posthumously published "New York Blues" (1970), a haunting character study of a man who may (or may not) have killed the girl he loved, is Woolrich at his bleakest. Woolrich's biographer, Francis M. Nevins, gave perhaps the best description of the lonely, tormented man who became noir's definitive practitioner. "He was," said Nevins, "the Poe of the 20th century, the poet of its shadows, the Hitchcock of the written word."

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

| Ellery Queen |

|---|

Probably no other name is more identified with the mystery short story in the 20th Century than the pseudonym adopted by cousins Manfred B. Lee (1905-1971) and Fredric Dannay (1905-1982) in 1929, when their first novel The Roman Hat Mystery, featuring a crime-solving mystery novelist who was also named Ellery Queen, was published.

Yet it was not until they had completed six more novels featuring Queen, and four additional novels as "Barnaby Ross" which featured actor-turned-sleuth Drury Lane, that the partners tried their hand at the short form. That first effort, "The Adventure of the One-Penny Black" (1933), was quickly followed by ten more Ellery stories, which were then almost immediately gathered together in their first collection, The Adventures of Ellery Queen (1934).

Like their novels, the Ellery shorts were crisply written, eminently readable, rigorously fair-play whodunits. Indeed, just as the Queen novels are widely regarded as perhaps the best book-length fair-play whodunits, their short stories are regarded as among the finest examples of fair-play detection in the short form. Over the rest of their career, the partners would write nearly seventy more short stories featuring their fictional doppelganger, along with at least one non-series short, "Terror Town," about a small rural community brought to the brink of panic by a serial killer.

They also wrote most of the episodes for an Ellery Queen radio series, which might be regarded as a form of short fiction in dramatic rather than prose form( especially since they adapted several of them into short stories), and dozens of true crime articles. In addition to Adventures, most of their remaining short fiction was collected in The New Adventures of Ellery Queen (1940), Calendar of Crime (1952), QBI – Queen's Bureau of Investigation (1955), Queen's Full (1965), QED – Queen's Experiments in Detection (1968), and The Tragedy of Errors (1999). Yet as fine as these stories were, the team's greatest contribution to short mystery fiction was not as writers of the form, but as editors, anthologists, and commentators on the form.

In 1933, the same year their first story was published, they started a new magazine, Mystery League, which they hoped would raise the literary level of short crime fiction. This worthy, but ill-fated effort died after four issues.

Over the next few years, the team (and particularly Dannay, though the collaborative pseudonym was used in all of their editing efforts) would start making a name for themselves as anthologists. Their first was the rather odd yet fun Challenge to the Reader (1938), in which stories featuring well-known detective characters were collected, with the names of the characters changed, and the authors' names concealed. Readers were then challenged to see if they could identify the character from their investigative styles.

This was followed by 101 Years' Entertainment (1941), which gathered together what they regarded as the finest crime stories written since Poe's invention of the genre with the 1841 publication of "The Murders in the Rue Morgue"; Sporting Blood (1942), which featured mysteries revolving around sports; The Female of the Species (1943), collecting stories featuring female detectives and criminals; and The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes (1944), featuring parodies and pastiches of Conan Doyle's immortal character, all followed in quick succession. Over the next forty-odd years, the cousins (or Dannay wholly on his own after Lee's death) would edit more than 80 different anthologies.

Aside from their prodigious work as anthologists, they took another stab at magazine publication in 1941. This second attempt, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, was far more successful than Mystery League and remains to this day the single most important periodical devoted to short crime fiction.

Because of their stature as editors, their opinions on short crime fiction are regarded as near-Scriptural. The Detective Short Story (1942), a bibliography of important short story collections; Queen's Quorum (1953), a more comprehensive list with commentary; and In the Queen's Parlor (1957), a collection of introductions to stories that had appeared in EQMM, are sought after by collectors as much for their scholarly content as for their rarity and high value.

But EQMM itself was undoubtedly their most effective vehicle for upgrading the status of short mystery fiction. Thanks to their magazine, the short fiction of Dashiell Hammett was preserved from the decaying pulps in which they had first appeared, making it possible for later collections to be gathered. Thanks to their magazine, Roy Vickers's relatively obscure series of inverted stories featuring a fictional cold case squad at Scotland Yard called the Department of Dead Ends had a ready market and became one of the benchmarks of short crime fiction. Thanks to their magazine, writers like Ross Macdonald, Stanley Ellin, Harry Kemelman, Richard Levinson and William Link, Kay Nolte Smith, David Morrell, Stephen King, and Nancy Pickard all had a place to be discovered. Thanks to their magazine, over 700 writers have had a market where their first piece of fiction could be published. Thanks to their magazine, African-American writer Hughes Allison had a market that would accept his story "Corollary," a police procedural about a black homicide detective, ten years before Chester Himes wrote the first novel to feature Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones, and twenty years before John Ball wrote the first novel to feature Virgil Tibbs. Thanks to their magazine, major literary figures not generally associated with mysteries, such as Rudyard Kipling, William Faulkner, Pearl S. Buck, John Steinbeck, Arthur Miller, Norman Mailer, Ernest Hemingway, and Alice Walker were all able to try their hands at crime fiction.

Virtually every sub-genre of crime fiction, from hardest of hard-boiled PI's to the softest cozies, from the most grittily realistic police procedurals to the wildest fantasies, from spy stories with international implications to stories set in a single room, from fair-play whodunits to criminal protagonists, have been published in EQMM. Virtually every important mystery writer who ever wrote a short story, from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to Mickey Spillane, from Agatha Christie to Ian Fleming, from Margaret Millar to Michael Avallone, from Erle Stanley Gardner to Earl Derr Biggers, from Edgar Allan Poe to Ed McBain, have appeared at least once in EQMM.

In 1948, the team received the first MWA Edgar ever awarded in the short story category. They went on to win a second in the same category for 1950. At that time, the Short Story Edgar was not awarded for an individual short story, but for the best achievement in the short story field. That first award was for general continued excellence as short story writers and anthologists. The second was for ten years of successfully editing EQMM. Since 1954, the first year that the short fiction Edgar was awarded for an individual story, over 17 stories published in EQMM have won, and dozens have been nominated.

In 1960 the cousins were awarded the MWA's Grand Master title. Had they never edited a single mystery anthology, never written a single sentence of scholarly criticism on short crime fiction, never given a thought to publishing a mystery magazine, they would undoubtedly have been recognized just for their own impressive body of crime fiction. But their activities as the premiere editors of and proselytizers for short mystery fiction are their most distinguished contribution to our genre.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

|

| Stanley Ellin (1916-1986) |

|---|

Highly regarded as a writer of crime novels, including the Edgar-winning private eye novel The Eighth Circle (1958), the Edgar-nominated The Valentine Estate (1968), and Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall (1972), winner of France's Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, Stanley Ellin was one of the few popular, critically acclaimed mystery novelists who was actually better-known for his short stories.

Oddly, he was not a particularly prolific short story writer, managing only about one a year during nearly 40 years as a professional wordsmith. Yet the excellence of that relatively small output assures him of a place in the Hall of Fame. Indeed, had he written no other short story except his first, "The Specialty of the House" (1948), a wonderfully twisted and justly famous tale about an exclusive restaurant with a signature dish both delicious and sinister, it would have arguably qualified him for inclusion all by itself.

But his first story was not his last, and, while Ellin was never as productive as such contemporary short story specialists as Edward D. Hoch, Clark Howard, or Jack Ritchie, he did go to extreme lengths to make each annual short story as perfect as possible. After working out his plot, he would write the first page, then rewrite it, then rewrite it again. And again. And again. He would not even begin the second page until he had a perfect, and perfectly typed, first. Then he would repeat the process on each succeeding page until he reached the end.

Even Ellin admitted that this painstaking approach was "madness." But no one could argue with the results. Despite a relatively small output, he took a wider variety of approaches, covered a wider spectrum of subjects, and consistently reached a higher level of quality than many far more prolific writers. His stories ranged from comparatively straightforward whodunits like "The Crime of Ezekial Coen" (1963) to a kid's eye view of organized crime like "The Day of the Bullet" (1959), from a nifty variation on the "lady-or-tiger" dilemma in "The Moment of Decision" (1955) to one of the most imaginative murder methods ever used in fiction in "The Last Bottle in the World" (1968), from a character study of a successful actor who finds his success a kind of hell in "The House Party" (1954) to a typical story about murder with a show business background that isn't really typical at all in "Beidenbaur's Flea" (1960). Ellin also used his short fiction to tackle the issues of the day, capital punishment in "The Question" (1962), the prospect of unemployment in "Reasons Unknown" (1978), or the ethical consequences of economic development in "Unacceptable Procedures" (1985).

Every story Ellin wrote was completely different from every other story, and each story was a masterpiece. His professional peers recognized this time and again. Ellin won an Edgar for "The House Party," the first time an Edgar in the short story category had been awarded for an individual tale (in previous years they had been awarded to collections, magazines, anthologies, or merely for continued excellence). Two years later he walked off with a second Edgar in the same category for "The Blessington Method" (1956). His aforementioned Edgar for Best Novel for The Eighth Circle made it a hat trick.

He was nominated four more times in the short story category, for "The Day of the Bullet," "The Crime of Ezekial Coen," "The Last Bottle in the World," and "Graffiti" (1983). In 1969, he was elected President of the MWA in recognition of his accomplishments in crime fiction. And in 1981, he received the MWA's greatest honor, the title of Grand Master. No short story writer ever achieves actual perfection, but no short story writer ever tried harder to achieve it than Stanley Ellin. And few came closer.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

| Edward D. Hoch (1930-2008) |

|---|

In 1950, Edward D. Hoch, a young man serving his stint of Army duty as a Military Policeman at Fort Jay in New York Harbor, began attending the monthly MWA chapter meetings in Manhattan, and joined the organization as an affiliate member. Over the next few years, as he returned to civilian life, moved back to his home town of Rochester, New York, and found work as an advertising copy writer, he strived to upgrade his membership status to "active" by getting at least one of his short mysteries published, but, like many a novice writer, spent several years collecting rejections slips before making a sale.

That first story, "Village of the Dead," was published in 1955 and introduced Simon Ark, a supernatural detective (he's a 2000-year-old Coptic priest) who solves non-supernatural crimes. "Village" was the first of nearly 1,000 short mysteries Hoch would write over the next half-century, and Ark the first of over two dozen series characters who would star in many of those stories.

The variety of different detectives he created gives an idea of the breadth of approaches he was able to take within the genre. There was virtually no sub-genre of crime fiction Hoch did not write. Police procedurals, featuring perhaps his most popular series character, Captain Jules Leopold, the commander of the homicide detail in an upstate New York police force, formed a large part of his output. But he also wrote hard-boiled private eye stories featuring California gumshoe Al Darlan; small-town "cozies" featuring physician and amateur sleuth Sam Hawthorne; spy stories featuring British Intelligence code expert Jeffery Rand; criminal protagonist stories featuring professional thief Nick Velvet; international thrillers featuring Sebastian Blue and Laura Charme of Interpol; religious detective stories featuring Father David Noone, a crime-solving Catholic priest in the tradition of Chesterton's Father Brown; historical mysteries featuring Alexander Swift, George Washington's chief intelligence officer during the American Revolution; western-mystery hybrids featuring Ben Snow, an itinerant gunfighter in the tradition of Shane or Paladin who is also a deductive genius; and many more.

He was also adept at writing about the characters of other writers. In his long career he wrote such pastiches as "Essence D'Orient" (1988), featuring Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe; "Chessboard's Last Gambit" (1990), featuring Chester Gould's Dick Tracy; "The Circle of Ink" (1999) and "The Wrightsville Carnival" (2005), both featuring Ellery Queen's "Ellery Queen"; and "The Return of the Speckled Band" (1987), "The Christmas Client" (1996), "The Case of the Anonymous Author" (2001), and "A Scandal in Montreal" (2008), among several others, all featuring the Master of Baker Street himself, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes. There were also hundreds and hundreds of stand-alone stories.

Whatever detective he was writing about, series or non-series, what almost all his stories had in common was a strict adherence to fair-play puzzles, an adherence that rivaled the similar commitment of his mentor(s), Ellery Queen. Hoch was particularly adept at the "locked room" or "impossible murder" story, built around a crime that couldn't have happened, but did, and not only happened, but turned out to have a perfectly reasonable explanation for how it happened. His facility for this kind of story, displayed in tales like "The Tomb at the Top of the Tree" (1969), "The Leopold Locked Room" (1971), "The Problem of the Covered Bridge" (1974), and "The Flying Fiend" (1982), was comparable to John Dickson Carr's, and he actually wrote more short stories in this vein than Carr himself.

Hoch's best-known, most frequently reprinted, and arguably finest story is probably "The Oblong Room" (1967), an entry in the Leopold series for which Hoch received the Edgar. The same year he won the award, Hoch quit his day job and became a full-time free-lancer, one of the very few authors able to make his living exclusively from short stories, and perhaps the only one making that living exclusively on short crime fiction. But he was up to the challenge.

He made his first sale to EQMM in 1962. 11 years later, in the May 1973 issue, he began a streak that lasted for over 35 years. From that date until several months after his death, Hoch had a story in every single issue of EQMM, making him the short mystery equivalent of Lou Gehrig or Cal Ripken, crime fiction's "Iron Man." Hoch's voluminous output and popularity with readers provided a ready source of material for collections and a ready market for those collections. Some of the best of the many volumes collecting Hoch's work include Leopold's Way (1985), The Quests of Simon Ark (1985), Diagnosis: Impossible (1997), The Ripper of Storyville (1997), The Old Spies Club (2001), and The Velvet Touch (2001), all devoted to one or another of Hoch's series sleuths, and The Night, My Friend (1992) and The Night People (2001), both devoted to Hoch's non-series work.

In addition to his own collections, Hoch's broad knowledge of the mystery genre in general, and the short mystery in particular, led to his becoming a very active anthologist. He was the editor of Dear Dead Days (1972), an anthology of historical mystery fiction, and All But Impossible! (1982), an anthology of locked room mysteries. In 1976 he replaced Allen J. Hubin as the regular editor of Dutton's annual Best Detective Stories of the Year series, holding that post through 1981, then continuing in the same position through 1995 after the series moved to Walker, and changed its name to The Year's Best Mystery and Suspense Stories. He also edited Murder Most Sacred (1989), devoted to mysteries with a Roman Catholic background (Hoch was a devout, practicing Catholic), and a general survey of US crime fiction for Oxford University Press, Twelve American Detective Stories (1997).

The Edgar Hoch won for "The Oblong Room" was only the first of many awards he'd earn for his short fiction. Another Leopold story, "The Most Dangerous Man Alive" (1980), was nominated for a short story Edgar. He also won two Anthonys at Bouchercon, the World Mystery Convention, the first for "One Bag of Coconuts" (1998), a Rand story, and the second for "The Problem of the Potting Shed" (2000), which featured Dr. Hawthorne. After literally dozens of nominations, but never a win because his many eligible stories had the effect of putting him in competition with himself, he finally won a posthumous Ellery Queen's Reader Award for a Nick Velvet story, "The Theft of the Ostracized Ostrich" (2007). His brother and sister MWA members elected him National President in 1982, in recognition of his eminence in the field. He also was presented with four different lifetime achievement awards, the first Golden Derringer ever awarded by the SMFS in 1999, the Eye from the Private Eye Writers of American in 2000 for his Al Darlan series, the Grand Master from MWA in 2001, and a Lifetime Achievement Anthony, also in 2001.

After his passing, in recognition of his achievements in short crime fiction, the SMFS, with the permission of Hoch's widow, Mrs. Patricia Hoch, changed the name of its Lifetime Achievement award to the Edward D. Hoch Memorial Golden Derringer. It's hard to believe he could have had time, given the incredible number of short stories he wrote, but Hoch did occasionally write novels. It was, however, never a task that he undertook with great enthusiasm. His first love, both as a reader and writer, was the short story. Of that form, he once said, "Writing a short story is a pleasure one can linger over, with delight in the concept and surprise at the finished product." Throughout his career, Hoch provided his fans with many moments of delight and surprise at his finished product.

| ⇪ Top | — Jim Doherty |

|

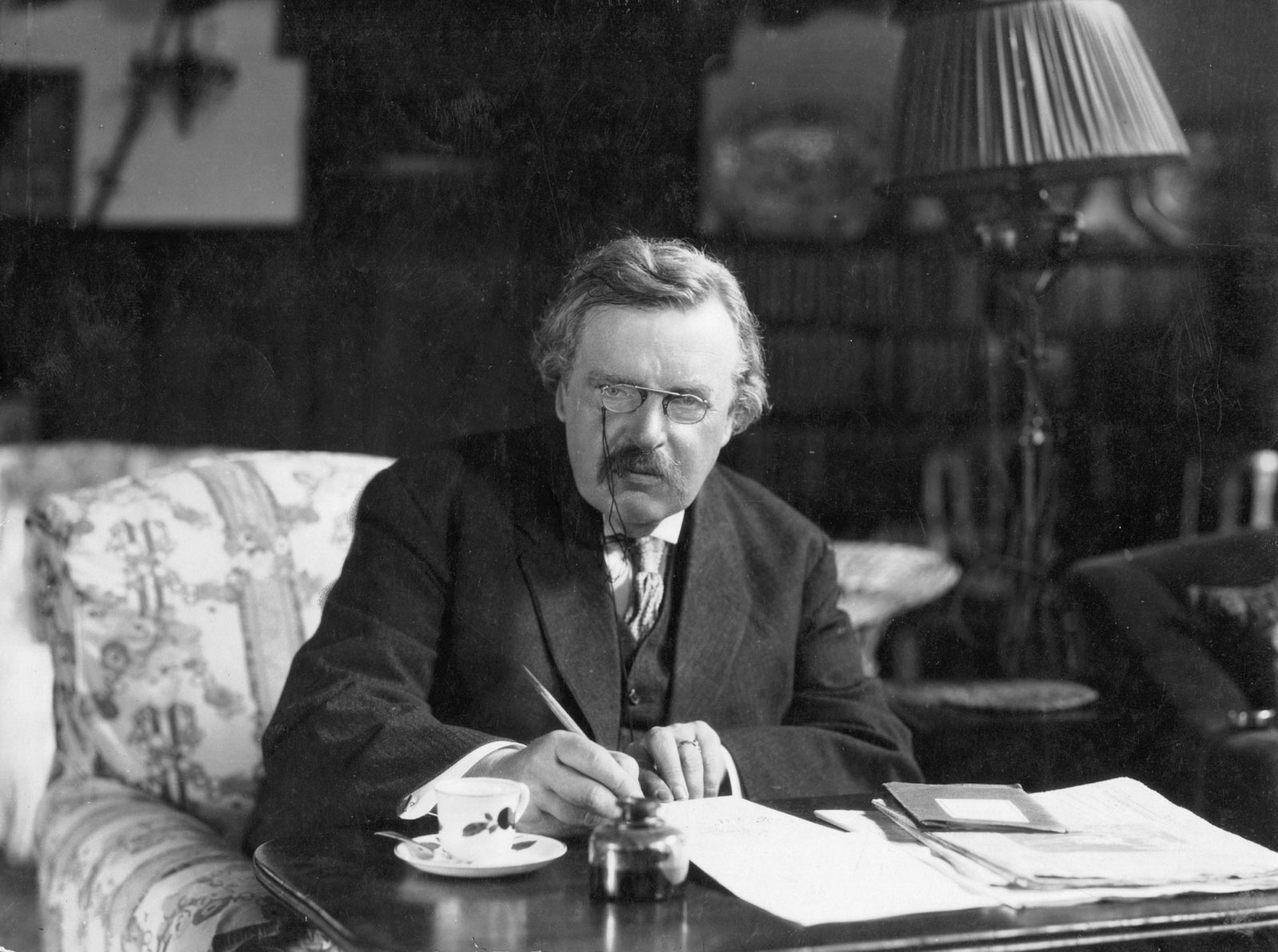

| G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) |

|---|

Chesterton was one of the leading authors of short crime fiction. His Father Brown, a humble Catholic priest, is one of the few great detective characters who exists only in short stories. The cleric made his first appearance in “The Blue Cross” in 1910 and solved crimes in more than fifty tales over the next 26 years.

Chesterton wrote several other volumes of short crime fiction, including The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and The Poet and the Lunatics. His novel The Man Who Was Thursday is both spy tale and a work of religious philosophy.

He wrote in many genres, including literary criticism, history, economics, and politics, and was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1935. His wealth of writing includes 80 books, several hundred poems, approximately 200 short stories, 4,000 essays, and several plays. His paradoxical style and humor allowed him to highlight many of the issues of his day including disregard for the poor, acceptance of eugenics, and the advancement of modernism.

He was also a pivotal figure in the mystery genre, serving from 1930-1936 as the first president of the Detection Club, a society of British mystery authors founded by Anthony Berkeley in 1928. Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers both credited his work as a major influence on their own. Other notable figures such as W.H. Auden, Jorge Luis Borges, Anthony Burgess, Karel Capek, Neil Gaiman, Mohandas K. Gandhi, Graham Greene, Ernest Hemingway, C.S. Lewis, and Orson Welles have cited him as an influence on their own work and worldviews. His books are still in print and Father Brown is a popular BBC TV series.

| ⇪ Top | — Tony Rudzki and Rob Lopresti |

.jpg) |

| Rex Todhunter Stout (1886-1975) |

|---|

Rex Todhunter Stout (1886-1975) was the creator of the unforgettable character of Nero Wolfe, the seventh-of-a-ton, beer-drinking, orchid-collecting private investigator. Wolfe, who rarely left his W. 35th Street Manhattan brownstone, relied on right-hand-man Archie Goodwin to do his legwork for him, sometimes calling in assistance from independent operatives Saul Panzer, Fred Durkin, and Orrie Cather. Also part of the Wolfean household were Swiss chef Fritz Brenner and orchid-master Theodore Horstmann, and frequent antagonists included Inspector Cramer of NYPD Homicide, Cramer’s assistant Sergeant Purley Stebbins, Lieutenant George Rowcliff, and master criminal Arnold Zeck. Other characters populating Wolfe’s world were Archie’s sort-of-girlfriend Lily Rowan, Gazette reporter Lon Cohen, attorney Nathaniel Parker, and Dr. Edwin Vollmer.

Stout was born in Indiana and raised in Kansas, attended the University of Kansas briefly, served in the Navy from 1906 to 1908, and then worked at various jobs before beginning his career as a professional writer in 1910 with the sale of a poem to a literary magazine. Around 1916, he came up with the idea for a school banking system that funded his travels around Europe and his comfortable lifestyle.

His first Nero Wolfe novel, Fer-de-Lance, was published in 1934, followed by another thirty-two novels and forty-one novellas and short stories, ending with A Family Affair in 1975. In addition to the Wolfe material (referred to by members of the Wolfe Pack, an active society of fans, as the “Corpus”), he also wrote several books in the Tecumseh Fox series, one each featuring Dol Bonner and Alphabet Hix, and occasional nonseries novels, such as his first full-length work, How Like a God (1929), which was unusually written in the second person. During the 1930s and ’40s, he was heard frequently on the radio, and he made numerous television appearances in the 1950s.

Stout was often involved in political and writers’-rights causes, serving on the board of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Council on Censorship in the 1920s, chairing the Writers’ War Board during WWII, and leading the Authors League of America during the McCarthy era. He served as president of the Mystery Writers of America in 1958 and received the MWA’s Grand Master Award in 1959. At the 2000 Bouchercon, the Corpus was nominated “Best Mystery Series of the Century,” and Stout himself was nominated “Best Mystery Writer of the Century.”

His first marriage, to Fay Kennedy, lasted from 1916 until they divorced in 1932, and he was married to designer Pola Hoffmann from 1932 until his death in 1975. He had two daughters with Pola: Barbara Stout Selleck (1933-2017) and Rebecca Stout Bradbury (1937- ).

(Vetted by Ira Matetsky, who runs the Wolfe Pack)

| ⇪ Top | — Josh Pachter |

| O. Henry (William Sydney Porter) (1862-1910) |

|---|

Though best remembered today for the Christmas story “The Gift of the Magi,” O. Henry’s hundreds of published short stories also include a huge number of influential crime narratives, including “The Ransom of Red Chief,” “The Cop and the Anthem,” and “A Retrieved Reformation.” A master of plotting and effective twist endings, O. Henry exemplified the depth, range and flexibility of the short story.

| ⇪ Top | — Joseph S. Walker |